Of Voting in 2024 (Part III of III): A System Which Feeds on Those it Pretends—by Pretense—to Protect.

"Masculine republics give way to feminine democracies, and feminine democracies give way to tyranny." —Aristotle, Politics

Part I focused on the concept of voting one’s “self-interest”—perceived or otherwise—while Part II took a look at the negative concept of “positive democracy”, i.e. democracy exercised for its own sake as if it were an end in itself (emanating from a positive view of human nature), rather than merely the reluctant means to achieving the end of good governance, free from the horrors of abject tyranny that in every age threatens to encumber, plague, and swallow up whole, human civil society (which is almost always centered around some formulation of civil government).

Part III wishes to take a deeper look at the underlying assumptions which support and undergird the drive by all entrenched institutional interests—from the state itself, to the media, schools, business corporations, and large-scale entertainment apparatuses (like Hollywood and various professional sports leagues)—to universally, and in an exercise of united lockstep (as if what we were witnessing was a socio-political ensemble being played out on the stage of modern civil society), push people towards the ballot box in a bid for widespread civic engagement. Such an overarching drive towards the polls seems to have—for such interests as those alluded to above—taken on a quasi-religious significance. Consider the following plea to protect our “democracy”, which, I think, features a startling but implicit undertone that is attempting to subvert our rational mind on the basis of emotion, to the end of imparting an unstated assumption that democracy—exercised as an institutionalized form of civil government—is essentially, in and of itself, hallow: i.e. sacred:

In the “canned news” above, there lies an implicit declaration that democracy itself is sacrosanct, and therefore necessarily deserving—for its own sake—of our protections (presumably whatever the cost); such a quasi-religious metaphysical tenet is both blasphemous and fatalistic in that such an aphorism bares for all to see, our unstated apathetic nihilism: on the one hand, it is an admission of our idolatry—a brazenly-glaring “slip of the tongue”, wherein our degraded, scientific and material age of secularism exalted—wherein the atomized consumer-citizen admits of himself, that he views the omnipotent and all-encompassing state as the closest remaining approximation of “God”. Thence, political activity embodies a proximate pseudo-religious association and quality, which is spiritually dissolving to the individual: it is if man bathed in acid and called it “holy water”.

I suppose in such a pluralistic and secular society with no overarching meta-narrative to bind us to our fellows, participation in statecraft—no matter how passive—becomes, itself, a ritualistic and “sacramental act” of acquiescent consent: a consent from which the socio-political state—on the federal and state levels—derives its authenticity and legitimacy. This is not to say that consent entails merely voting for the “winning” candidate before whom we would prostrate ourselves willingly and voluntarily, but rather that the act of voting itself shows faith in the institutional apparatus of government itself, which unconsciously implies a belief in the veritable viability of the state itself, which then underlies an assumption that in some remote capacity, such a state is (still) fulfilling its modus operandi. But what happens when a state ceases to largely fulfill its primary functions and secondary obligations?—when a state prioritizes its own institutional interests over that of its constituents? And further, what happens when such a state is so large, vast, interconnected, and otherwise levianthic that it can no longer be forcibly resisted? As sitting president, Joe Biden, warned us, stating:

“If you wanted or if you think you need to have weapons to take on the government, you need F-15s and maybe some nuclear weapons. The point is that there has always been the ability to limit — rationally limit the type of weapon that can be owned and who can own it.”

And so, we have reached the decisive point in our three-part inquiry into the nature and veracity of the ritual-act of voting in the year 2024—and why I believe not only a fruitless endeavor, but an ensnaring one at that (for a multitude of reasons). Foremost, the latter declaration—i.e. that participation in statecraft via voting in the age of mass society is, itself, a fruitless endeavor—brings me to an observation: it is in the age where government is as wicked and dysfunctional as ever, that there exists a seemingly (at least on the surface of things) confounding but incessantly ubiquitous drive (that seems to be increasing in scope and magnitude each passing election cycle) by the dehumanized system itself, to push for everywhere—via every communicative medium available to it—political engagement, exercised for its own sake (as if political engagement were of a spiritual, quasi-religious importance).

I do not think the former may be understated: for it has become an overarching tenet of our society, which feels as though no woman, man, or child cannot simply be left alone, or to his or her own devices: we used to be a society of private individuals—i.e. individuals that lived and let live—who freely pursued their own ends given that they did not harm others or society at large. But we have increasingly become a digitally-interconnected but physically-disconnected “community” of individual moral “busy-bodies” that aggregate online into echo chambers, from which they branch out into the artificial world which we have created for ourselves to be contained by, casting aspersions of feigned moral concern that necessitate intervention, which then precludes anyone from merely being—or being left alone. This, I think, is the origin of the shift in recent decades, towards viewing the mere act of writing in—or connecting fragmentary lines—to indicate a preferred candidate for a given office, itself, an act of great civic virtue. It is almost as if people—when they post “selfies” afterwards on “social” media—are “boldly” (but in a way that seeks external validation and recognition) declaring: “Look at me: I voted!”; “I am, therefore, a good person—a good and obedient tax-paying citizen!” To me, such cringeworthy demonstrations of signaled “virtue” show a profound weakness and great spiritual defeated-ness; it is almost as if the individual—created distinctly and in the image of an omnipotent, omniscient, and consummately good God—has been fully absorbed, subsumed, and taken within the great degenerated mass.

I must declare it again: civil government itself—particularly a fully-secularized one at that—is not “holy”; therefore, the ritual act of going and casting one’s lot in the form of a vote is not “sacred” or “hallowed”, but decidedly hollow. It was, hitherto—on the appearance of things past and forgone—a good and dutiful thing to do (assuming one is properly informed and invested), but I think that no longer so: it is not merely that I feel unrepresented or unspoken for, but moreso that I believe that investedly participating in the system which feeds upon our very life-force and essential human energies—which to rule us effectively and completely as it increasingly does, requires us to be in a constant state of fear, paranoia, anxiety, and other neuroses, to maintain its power over our minds—to be antithetical to individual human flourishing, which is of a intellectual and psycho-spiritual orientation. We cannot, therefore, hope for government to save us from our sufferings—to salvate our souls: we instead must look immanently within, and eminently without, to hope to “achieve”, and be worthy of, such an aspirational effect.

If it’s not clear by now, I am inherently skeptical of such an activity: for political engagement is merely the means to secure the “end” of social, governmental, and civilizational harmony, but is never an “end unto itself”—even those aforementioned “fruits” of civilization, are themselves, ephemeral, transient, and fleeting: for what is won with greatly arduous toil, is soon lost with quick prolapse. But again, we must inquire: who is so well-informed and intentioned, that he or she would merit the “right to vote” and otherwise participate in government? I, for one, have no such time or energy to dedicate myself to the wholesale “study” of such dizzying and disorienting current affairs about which enough can seldom be known to dictate intervening action: such a sentiment is probably why I find myself gravitating towards the realm of ideas and history, both of which can be “verified” to some vague degree, owing to their fixed, “set in stone” nature. I would rather contend that it is mass political engagement itself—i.e. the mass phenomenon of mechanized propaganda begun by Bernays and others—that has allowed the truth to be so obfuscated,—and virtue, resultantly, to be extinguished and inverted thus (nearly everywhere, that is). Consider what to be plugged into the news, or current on affairs, actually entails: constant bombardment with pain, death, suffering, moral degeneracy, and cultural decay (for that is what sells and invokes attention)—always seeing and interacting with the chthonic, but missing the mundane but everyday miracle of embodied existence; what “good” is there in a continual flow of negative information? which only serves to keep the individual informed, insofar as it orients him or her towards groupthink and collective opinion, but which requires—for purposes of control—such informed people be kept dizzied with neurotically-scintillating information.

But, as I said above, we no longer live in a world that truly allows people to opt out or live their own lives free from the flow of (negative) “information”, which many say is the “currency” of democracy. And so, what we have is a ubiquitous push—which I think only serves the interests of the system itself, which needs voters, yes, but moreso obedient taxpayers—towards (wholly or partially) unwilling civil participation. Leave such people alone, I say! Let those who wish to be wrapped up in the news and election cycle be wrapped up and consumed by it—it is their “sacred” right to do with their lives what they choose: if they wish to eschew real life for such cosmically mean and inveterate affairs, let them!

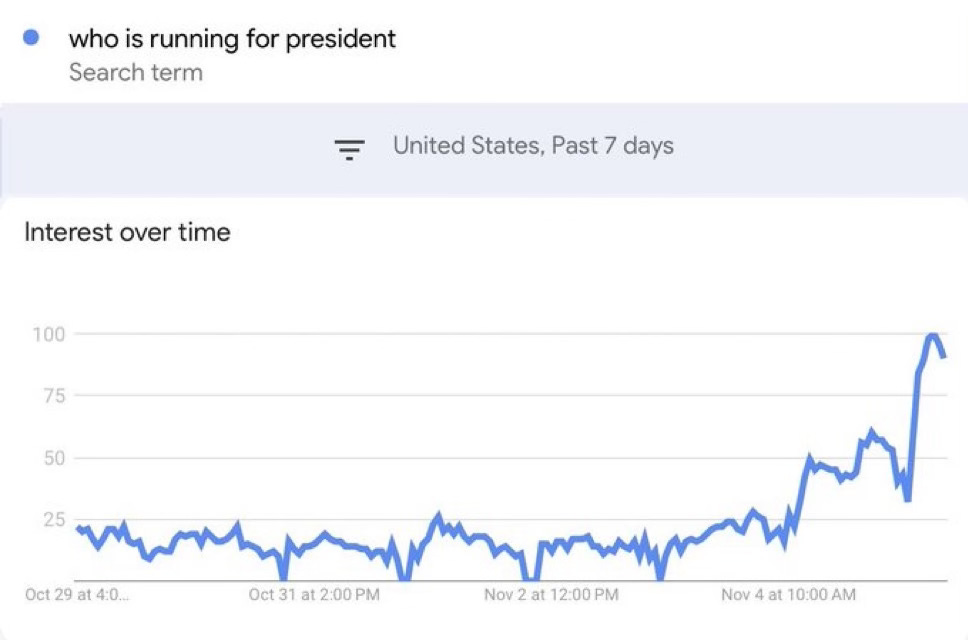

But can we also not have a bit of humor?—is not humor a partial antidote to chaos, misery, and suffering? Consider that we live in such a “nation of scholars” that in recent days—mere days before that great civic holiday, called “election day” on which we hang our dearest hopes and dreams for a future that will be better than the troubled present—that “who is running for president” has been trending on search engines:

Why should people such as these be goaded, encouraged—even shamed into voting? Why should we just not simply leave them alone, let them be, and leave them to their own devices, allowing them the opportunity—insofar as they do not harm others—to pursue their own private ends? If they wish to abstain, it is their right– and who are these audacious internet rousers to suggest they do otherwise than that which their slothen natures would allow? This is not to say that such people are irredeemable or in any way immoral; in fact, I think more people, who do not feel in within them to vote, should be told explicitly: if you don’t know nor care, the right, i.e. moral thing to do is to suspend judgment: for in the absence of a reasonable assumption of knowledge, admitting one’s unknowing and uncertainty is the right way forward. In such an estimation, I include myself: as that is precisely what I have chosen to do this time around—despite admonishments and incisive glares from friends and family—disenchanted with, and disillusioned by, all sides and their completely inept, ill-conceived “plans” for saving that which I love, but that which I fear is—at this point—largely unsaveable. And for my own individual path and attempt at flourishing, I chose to remove myself from contemporary politics post-2020, when it became clear the country I loved and believed in no longer really existed—and if I was being honest with myself: hadn’t for quite some time.

Please understand dear reader: the surest way to abject and complete tyranny is through democracy emboldened with centralized authority, standing armies, and an ineptly incompetent but pervasive bureaucracy—all of which constitute the very conditions of the contemporary (residual but retreating) West. Bearing Tocqueville in mind, one comes face-to-face with the truly horrifying specter of so-called “majority tyranny” (that I discussed in passing in the previous part of this essay); but I postulate, what we are witnessing is—owing the large-scale psycho-spiritual degradation of modern people—is perhaps even more alarming: for modern society possesses and embodies, an absurd principle—not in a spiritual and transcendentally paradoxical sense, where seemingly disparate ends may be woven together, e.g. as in Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling, but in a literal one; we have not only become untethered from our foundational preceptorial moorings, but have also become—quite literally—unhinged: psychologically, spiritually, religiously, socially, culturally, physically, and otherwise. The human mind has indeed been “torn to shreds” and put back together in a new manner, of which we are largely unaware, but which most of us suspect.

What this means in practical application: base impulses and unconscious desires have been stoked through mechanization and subsequent wielding of propaganda (by which I include incessant advertising); such activities of “public relations” aim at undermining the rational mind through subversion, which has largely captured the minds of men and made them increasingly neurotic: i.e. irascible, despairing, anxious, and malleable, whereby the great mass of humanity is more aptly able shaped and molded by social-conditioners, always being an incapacitated subject, allowing him or her to be bent towards “ends” of which he or she neither knows nor chooses. This is, I think, the true human and individual cost of being constantly plugged-in to the purposefully-negative and misleading, 24-hour news cycle (and its “great public holidays”, of which the presidential election is the crown jewel).

And so, when one is faced with witnessing reality in real-time, consider the wholesale lack of control and agency that people who are caught up in it all, truly have: extend such fallen fellows grace and understanding, but do realize that such extensions of other people’s power are truly and terrifyingly dangerous to themselves, other people, and liberty far and wide. Such people, seeking the enaction of what they have been convinced is “right”—eschewing nuance and discernment—will employ drastic measures to achieve power; and the power which could very well ensue, will be but an iron-fisted enforcement of the “general will” of the ever-so-slight “majority”: a majority which is itself not noble or honorable in any traditional sense of those elevated concepts, but is instead seeking its own short-sighted advantage (i.e. within the timeframe of a mere four years, wherein no truly beneficent and restorative work may be accomplished) as it perceives it (based on largely unconscious factors of which it is unaware). All of this is to reiterate: democracy with centralized authority is the surest form of tyranny—which Plato and Aristotle knew with reasoned certainty 2,400 years ago, but which modern man has forgotten—but is an absurd one at that because the masses—goaded on from above and below—become increasingly apt and likely to descend in a downward spiral, towards an iron-fistedly enforced and prescribed, absurd madness. Such a mass phenomenon of “madness”—or perhaps, psychosis as in a delusional disconnect from reality—can be seen most vividly in the realm of “social issues”, where almost all human norms since the beginnings of western civilization have been radically uprooted, even inverted, in the last sixty some-odd years.

I realize what I am saying is likely to fall on deaf ears and only accomplish branding the author as the sole, fringe lunatic in an otherwise functioning but imperfect mass society: to them I say, you may well be right, but first hear me out, because social phenomena and long-standing trends are almost never as they appear on the surface of things.

Edward Bernays and “The Century of the Self” Obsession: i.e. the Concept of Extrinsically-Derived Identity

E.g. the public consciousness should always bear in mind and heed, these callous, hyper-rationalistic, disimpassioned—but insidiously manipulative—words from the “Father of Public Relations”, Edward Bernays, (who was nephew to psychoanalyst, Sigmund Freud, and an instrumental “guiding-hand” and “man behind the curtain” in the “war” fought to capture and captivate the minds of men), who within twentieth century mass society—with its hallmarks being an increased organization of labor under corporatism, collectivism, and the otherwise wholesale centralization of power—was a giant in the burgeoning world of orienting the public mind towards desired, but foregone and pre-ordained, conclusions :

The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country.

We are governed, our minds molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of. This is a logical result of the way in which our democratic society is organized. Vast numbers of human beings must cooperate in this manner if they are to live together as a smoothly functioning society.

Our invisible governors are, in many cases, unaware of the identity of their fellow members in the inner cabinet.

They govern us by their qualities of natural leadership, their ability to supply needed ideas and by their key position in the social structure. Whatever attitude one chooses toward this condition, it remains a fact that in almost every act of our daily lives, whether in the sphere of politics or business, in our social conduct or our ethical thinking, we are dominated by the relatively small number of persons—a trifling fraction of our hundred and twenty million—who understand the mental processes and social patterns of the masses. It is they who pull the wires which control the public mind, who harness old social forces and contrive new ways to bind and guide the world.

It is not usually realized how necessary these invisible governors are to the orderly functioning of our group life. In theory, every citizen may vote for whom he pleases. Our Constitution does not envisage political parties as part of the mechanism of government, and its framers seem not to have pictured to themselves the existence in our national politics of anything like the modern political machine. But the American voters soon found that without organization and direction their individual votes, cast, perhaps, for dozens of hundreds of candidates, would produce nothing but confusion . . . In theory, every citizen makes up his mind on public questions and matters of private conduct. In practice, if all men had to study for themselves the abstruse economic, political, and ethical data involved in every question, they would find it impossible to come to a conclusion without anything. We have voluntarily agreed to let an invisible government sift the data and high-spot the outstanding issue so that our field of choice shall be narrowed to practical proportions. From our leaders and the media they use to reach the public, we accept the evidence and the demarcation of issues bearing upon public question; from some ethical teacher, be it a minister, a favorite essayist, or merely prevailing opinion, we accept a standardized code of social conduct to which we conform most of the time.

In theory, everybody buys the best and cheapest commodities offered him on the market. In practice, if every one went around pricing, and chemically tasting before purchasing, the dozens of soaps or fabrics or brands of bread which are for sale, economic life would be hopelessly jammed. To avoid such confusion, society consents to have its choice narrowed to ideas and objects brought to its attention through propaganda of all kinds. There is consequently a vast and continuous effort going on to capture our minds in the interest of some policy or commodity or idea.

It might be better to have, instead of propaganda and special pleading, committees of wise men who would choose our rulers, dictate our conduct, private and public, and decide upon the best types of clothes for us to wear and the best kinds of food for us to eat. But we have chosen the opposite method, that of open competition. We must find a way to make free competition function with reasonable smoothness. To achieve this society has consented to permit free competition to be organized by leadership and propaganda. Some of the phenomena of this process are criticized—the manipulation of news, the inflation of personality, and the general ballyhoo by which politicians and commercial products and social ideas are brought to the consciousness of the masses. The instruments by which public opinion is organized and focused may be misused. But such organization and focusing are necessary to orderly life.

—Edward Bernays, Propaganda, 1928

Though Bernays bore for all (in the above passage), the true underlying reality of our “free market”, capitalistic system, his words should disconcert us all. While today he is little-known, Bernays was a permanent fixture of twentieth century business and politics; among his many “accolades”, Bernays—who repurposed Freud’s psycho-analytic methods to undermine and placate (unknown and unrealized) desires of the unconscious—is “credited” with getting women to smoke cigarettes, through a campaign where he attached rebellious psychic-significance to the act of smoking itself, where the former became a “freedom torch”: i.e. a symbol of great—imaginary and intangible—but rebellious psychological power. Unfortunately for us, he also used his “talents” for many other subversive and questionable “ends”, such as promoting the “American Breakfast” of eggs, bacon, and pancakes—as well as lobbying for the addition of fluoride to municipal water supplies across the nation to “combat dental caries.” In short, Bernays was frequently employed by corporations and government alike, to subvert the unconscious mind of the American citizen—often using doctored statistics and data to achieve his desired, “evidence-based” results. The contemporary philosopher, Noam Chomsky, frequently discusses Bernays—and even wrote a book largely about Bernays entitled, Manufacturing Consent:

To See Where We Are Going, We Must Know From Whence We Came

Consider, to the contrary, these virtuous and manly words, in which genuine moral concern for the well-being of the world and the people in it, is palpably apparent:

Are people becoming, or likely to become, better or happier? Obviously this allows only the most conjectural answer. Most individual experience (and there is no other kind) never gets into the news, let alone the history books; one has an imperfect grasp even of one’s own. We are reduced to generalities . . . More useful, I think, than an attempt at balancing, is the reminder that most of these phenomena, good and bad, are made possible by two things . . . The first is the advance, and increasing application, of science. As a means to the ends I care for, this is neutral. We shall grow able to cure, and to produce, more diseases –bacterial war, not bombs, might ring down the curtain– to alleviate, and to inflict, more pains, to husband, or to waste, the resources of the planet more extensively. We can become either more beneficent or more mischievous. My guess is we shall do both . . . The second is the changed relation between Government and subjects . . . On the humanitarian view all crime is pathological; it demands not retributive punishment but cure. This separates the criminal’s treatment from the concepts of justice and desert. . . Thus the criminal ceases to be a person, a subject of rights and duties, and becomes merely an object on which society can work. As a result, classical political theory, with its Stoical, Christian, and juristic key-conceptions (natural law, the value of the individual, the rights of man), has died. The modern State exists not to protect our rights but to do us good or make us good — anyway, to do something to us or to make us something. Hence the new name ‘leaders’ for those who were once ‘rulers’. We are less their subjects than their wards, pupils, or domestic animals. There is nothing left of which we can say to them, ‘Mind your own business.’ Our whole lives are their business.

I write ‘they’ because it seems childish not to recognize that actual government is and always must be oligarchical . . . But the oligarchs begin to regard us in a new way. Here, I think, lies our real dilemma. Probably we cannot, certainly we shall not, retrace our steps. We are tamed animals and should probably starve if we got out of our cage . . . But in an increasingly planned society, how much of what I value can survive? I believe a man is happier, and happy in a richer way, if he has ‘the freeborn mind’. But I doubt whether he can have this without economic independence, which the new society is abolishing. For economic independence allows an education not controlled by Government; and in adult life it is the man who needs, and asks, nothing of Government who can criticise its acts and snap his fingers at its ideology . . . Who will talk like that when the State is everyone’s schoolmaster and employer? Admittedly, when man was untamed, such liberty belonged only to the few. I know. Hence the horrible suspicion that our only choice is between societies with few freemen and societies with none. Again, the new oligarchy must more and more base its claim to plan us on its claim to knowledge. If we are to be mothered, mother must know best. This means they must increasingly rely on the advice of scientists, till in the end the politicians proper become merely the scientists’ puppets. Technocracy is the form to which a planned society must tend. Now I dread specialists in power because they are specialists speaking outside their special subjects. Let scientists tell us about sciences. But government involves questions about the good for man, and justice, and what things are worth having at what price; and on these a scientific training gives a man’s opinion no added value.

—C.S. Lewis, “Is Progress Possible: Willing Slaves of the Welfare State,” 1958.

Opting Out, or the Way Forward

All of the previous, brings me to a decisive point in our inquiry: would we not be better off if we merely tended to—and were allowed to—“cultivate our gardens”?; was the former not the original promise of liberalism and its accompanying system of free enterprise? I think it no exaggeration to state: the current system feeds on well-intentioned human beings; to such an end, it uses any and all participants for its own purposes: the previous includes criminals and illegal aliens—who help serve a “greater” purpose of keeping the population in a constant state of miserable neuroses, i.e., anxiety, depression, fear, and perhaps even terror (at times)—all of which serve to justify, the continued existence of the leviathan itself, for the sake of “ameliorating” the very problems it has created. The current American system then, does not operate for the benefit of such goodhearted people, but rather at their expense. How ought we go about changing such a state of affairs?—surely not by engaging with it, all the while placating ourselves to its insidious games?

What is Man? What Does He Need to Flourish?

Man is a spiritual creature: encumber, weaken, and plague his spirit, and he (or she) will wither and die the worst of slow deaths—even if he retains the vestiges of physical life: if no other reasons have caused you to question, consider seriously, this one. Proceeding from such a first principle, this is why I believe attempting to take part in modern statecraft is a fruitless endeavor that will only thieve one’s life-force that could be directed elsewhere: for it is hopelessly thwarting to continually engage in, and be consumed by, such overarching realities in which the powerless individual cannot help affect in any meaningful way. It was probably during the latter-half of the nineteenth century that political engagement—if it hoped to change anything—necessarily required mass organization, cooperation, and a united principle of “satyagraha”, whereby disparate peoples willingly and peacefully, choose to arrange themselves around a common cause; but in such mass movements, there lies an inherent narrowing of scope of what changes are truly possible without revolutionary upheaval, which itself almost always causes more harm than good. Therefore, repeatedly engaging in modern politics, via menial and passive methods, ensures that disconnected individuals will—almost undoubtedly—grow frustrated by the lack of tangible and palpable change; I therefore believe, to continually do the latter is the surest way to misery and spiritual ruination for the individual: for we have allowed them, i.e. the degraded oligarchy which rules, to tear us apart for their own meager purpose. As a result of our current circumstance, the most radical act that we can therefore do, is to love our neighbor—to give of ourselves to the benefit of our countrymen.

As I alluded to earlier, voting is an inherently passive “activity” that encourages the individual, atomized within the mass, to merely “come out of the woodwork” every so often, to cast his or her “sacred” vote, making one’s “voice heard”; but then—as if it were all a ruse—we must then return to a passive and thwarted life of watchful but inactive receptivity, allowing corrupt governance to commence. All of the preceding hinges on acknowledgment of the unsettling reality within the modern world of globalized civilization—whereby most people indeed do live physically-separate “online” lives of constant “connection”—and further: it is the system itself that beckons and summons us to do just that, ceasing everywhere in the “world of civilization” to refrain from living in the “real” world of nature, i.e. what was hitherto regarded as consummate reality itself—where form and substance, matter and animation, melded and met, in one.

But now, we are increasingly disembodied form—floating aimlessly in the web of decontextualized and cacophonic information, of a discordant but entangled connectivity—no longer grounded to earth, to nature, nay to a real, tangible material existence mired, but set in rock and mud, in grass and sand, in stream and expansive plain; all of the above, with its poetic license, is to say we live almost entirely artificial lives within a great and expansive digital artifice that we have conflated with the “thing itself”, i.e. the real world of a posteriori experience. We are therefore, increasingly inhuman in every traditional sense or meaningful signification of the conceptual term; the former gives living animation to Orwell’s declaration: “the proles (i.e. those living beyond the pale of contemporary human society) are human—we are not human”. Further, we fight one another for scraps—nay, we fight each other for "cooking pots and rations in the streets", rather than uniting to fight the real enemy which are those parasitical forces that prey upon the mass of humanity and its constant fear, dread, anxiety, and suffering.

What mattered were the individual relationships, and a completely helpless gesture, an embrace, a tear, a word spoken to a dying man, could have value in itself. The proles, it suddenly occurred to him, had remained in this condition. They were not loyal to a party or a country or an idea, they were loyal to one another. For the first time in his life he did not despise the proles or think of them merely as an inert force which would one day spring to life and regenerate the world. The proles had stayed human. They had not become hardened on the inside. They had held onto the primitive emotions which he himself had to relearn by conscious effort. And in thinking this he remembered, without apparent relevance, how a few weeks ago he had seen a severed hand lying on the pavement and had kicked it into the gutter as though it had been a cabbage stalk.

—George Orwell, 1984

He remembered how once he had been walking down a crowded street when a tremendous shout of hundreds of voices–women’s voices–had burst from a side-street a little way ahead. It was a great formidable cry of anger and despair, a deep loud ‘Oh-o-o-o-oh!’ that went humming on like the reverberation of a bell. His heart had leapt. It’s started! he had thought. A riot! The proles are breaking loose at last! When he had reached the spot it was to see a mob of two or three hundred women crowding round the stalls of a street market, with faces as tragic as though they had been the doomed passengers on a sinking ship. But at this moment the general despair broke down into a multitude of individual quarrels. It appeared that one of the stalls had been selling tin saucepans. They were wretched, flimsy things, but cooking-pots of any kind were always difficult to get. Now the supply had unexpectedly given out. The successful women, bumped and jostled by the rest, were trying to make off with their saucepans while dozens of others clamoured round the stall, accusing the stall-keeper of favouritism and of having more saucepans somewhere in reserve. There was a fresh outburst of yells. Two bloated women, one of them with her hair coming down, had got hold of the same saucepan and were trying to tear it out of one another’s hands. For a moment they were both tugging, and then the handle came off. Winston watched them disgustedly. And yet, just for a moment, what almost frightening power had sounded in that cry from only a few hundred throats! Why was it that they could never shout like that about anything that mattered?

—George Orwell, 1984

How did we get here? How do we go back and begin anew from firm foundations?—once more leading human lives, keeping the good parts of the present, while eschewing most inhibitions and superfluities? I’m not sure, but I suspect that the way forward is to opt out, putting the onus and burden of action upon us: upon the individual, upon the family. I believe we have arrived at the present moment through the “mere”—to invoke that word that has become something of an unintentional motif throughout this work—passive and inactive, “voting the lesser of two evils”. The latter of which, when done for long enough—and extended outwards indefinitely, as has been the case in Western societies for decades—eventuates in the same destructive, denigrated, and debased place, as if evil were merely left unchecked, untrammeled; we have been playing games of pandering and placation—fighting over commonsensical premises, when we should perhaps be withdrawing, retreating, and forming a great undercurrent of high and lofty humane culture, that could everywhere speak to the “human condition”, offering potential ameliorations in a way which debased contemporary politics could never dream of. Edmund Burke famously told us, “evil prevails when good men do nothing”: voting, especially within the current framework, is not really doing something—and if it is, it is not something truly good.

A Shocking Conclusion?

All of the previous leads some escapist within my being to ask: what is to stop us from merely opting out en masse?; perhaps instead we could build—and retreat to—“parallel structures” of our own making, living in true community once again and seeking out life itself, “mean as it may show us to be” (as Emerson implored us). Remember, the current iteration of corporatized consumer-culture relies upon you! In fact, it necessitates a continual, participative process of production and consumption—from “cradle to grave”—which is measured in mere quantitative qualifications: that is to say, in merely impersonal and statistical economic terms, i.e. those of GDP.

Therefore, if we remain engaged, we remain entranced; if we remain entranced, we will never achieve nor fulfill our higher nature—our higher calling. We will, instead, be forever and perpetually dragged through the muck and mud, of the ever-descending and downward-spiraling, present. And so, I say: opt out!—find a way out! If “they” stop you—with hook, crook, or mere economics (as is presently being done)—find another way! Be resourceful! Do not give up, nor give in, but mostly do not delude yourself into thinking that we can passively “vote” our way out of societal suffering and tribulation. Bear all this in mind, dear reader, as you are forced to brave a litanous procession of endless political advertisements this (and every ensuing) election season! Most of all: do not allow them to demean and pander you, as though you were but an unruly child, carelessly and haphazardly braving the cereal aisle in the supermarket!—you are too great and lofty a creature to fall for such berating nonsense that is sure to thieve from you, your vital life-force!

Either way, if you choose to vote, do not merely vote your own interest. Instead, attempt to seek the advantage of all human civilization everywhere, no doubt—but do so in one’s own homeland first. Seek to resist and conquer not by force, but through the dual-application of the reasoned pen and trading purse; rejuvenate art, culture, and music: once more create again for creativity’s sake, but aim at “Truth”—unknowable as she may be. It takes individual action to make the world a better place: for that is one of the enumerable lessons of history. Every great movement, and every watershed moment, has shown that revivifying reification begins first with the individual, i.e. you—and me.

For these reasons, do not merely vote your own selfish self-interest!—and neither allow yourself to be the fuel that the inhuman machine runs on. Opt out of such illusory chains: for your life and higher being hinges on mental tranquility and spiritual well-being—which is precisely the joy which the cesspool that constitutes contemporary partisan politics wishes to thieve from you! But either way, dear reader, do know: if the twentieth century has taught us anything (and in this I am calling to mind those prison-camp philosopher-bards: Frankl and Solzhenitsyn), it is that the mind and higher being within us all can be liberated in the midst of torment, suffering, and great lament—with external circumstances that far outstrip our own—but only if one does look simultaneously up and within, seeking repose and reprieve from outer discord and socio-political rancor.