Prometheus Unbound: Mary Shelley’s Admonishment About Scientism (originally published 12/12/2019)

“I agree Technology is per se neutral: but a race devoted to the increase of its own power by technology with complete indifference to ethics does seem to me a cancer in the Universe. Certainly if he goes on his present course much further man can not be trusted with knowledge” —C.S. Lewis

“Learn from me, if not by my precepts . . . how dangerous is the acquirement of knowledge and how much happier that man is who believes his native town to be the world, than he who aspires to become greater than his nature would allow.” —Victor Frankenstein

The Relevance of Prometheus

In Romantic circles of the 19th century, allusions to the Promethean allegory “abounded.” Percy Shelley wrote Prometheus Unbound while Lord Byron wrote Prometheus. In response to her husband, Percy Shelley, and her father, the renowned William Godwin, Mary Shelley penned Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus. Percy and Godwin, and to a lesser extent Mary Shelley’s own mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, were cavalier provocateurs, social radicals and self-described atheists—who lived to push the envelope in their quest to “liberate” humanity from long-established social convention and hierarchies. Mary Shelley however, hearkened back to the more conservative, previous generation of Romantics, who grounded their enthusiasm for the natural world in Christianity.

In the Promethean Allegory, Prometheus is both hero and villain. In one ilk, he molded humanity (and then subsequently furnished humans with fire) out of clay to aid the titans in their struggle against the gods. While Prometheus is the benefactor and creator of humanity, his revolution against the divine order cost him dearly, as he was chained to a rock, whereby an eagle (the iconographized form of Zeus) would incessantly peck out and regurgitate his internal organs. Gruesome and grotesque was the punishment of Prometheus, though his revolution against the gods was the impetus for Mary Shelley’s Victor Frankenstein.

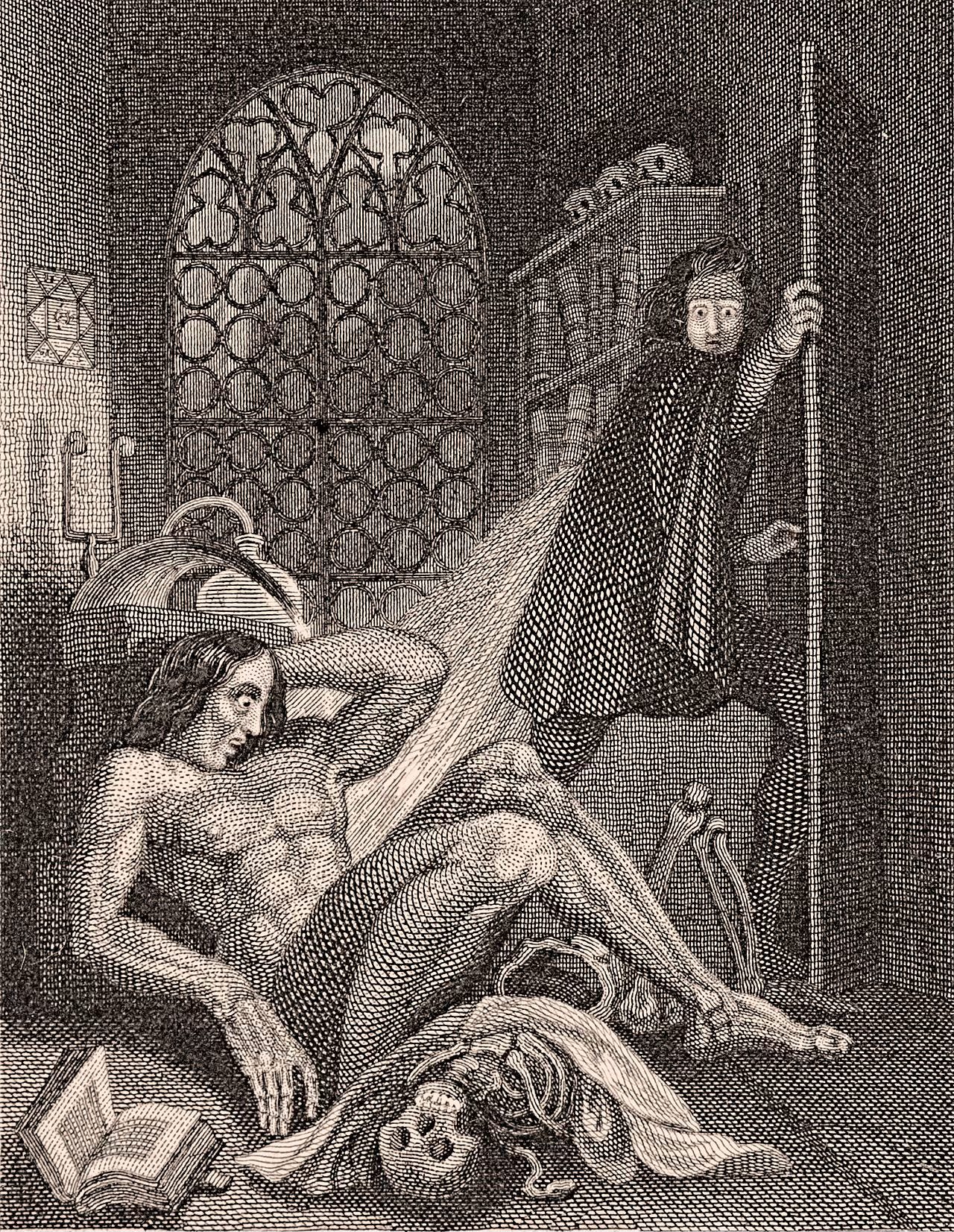

Frontispiece to Frankenstein, 1831 Edition

Francis Bacon: A True Prometheus

In the 17th century, Francis Bacon revolutionized epistemology with his radical empiricism, which spawned his Novum Organum, or “new instrument,” which we know today as the “scientific method.” In actuality, there was nothing new about it, as inductive reasoning or small truths coalescing together to form some semblance of a logical conclusion, had been practiced since the time of Aristotle or even before. What was new, however, was Bacon’s disdain for knowledge other than that ascertained through empirical means, observable and tested via the senses. Bacon deemed traditional social institutions and long-held philosophical convention as dogmatic and therefore erroneous. These inhibitions represented his four “idols,” which prevented the advancement of the “kingdom of man”—his words, not mine.

Bacon was the man who famously declared that “knowledge itself is power,” ushering in the new age of scientific management and applied science. The end of Baconian knowledge is power, and this is precisely why it is nefarious. Traditionally, power had been the means to some greater end: monarchs for instance, justified their absolute power (fallaciously) in a Hobbesian sense as a means to peace, social harmony, and order. Bacon, however, treats that which was traditionally a means as an end unto itself. This is what C.S. Lewis elucidates in Abolition of Man, when he states that what we are witnessing in the modern age is a rebellion of the “branches against the tree.” The tree then is Truth itself which is sacred as an end in itself. The branches are simply the means by which the final end of knowledge—or as this sort of knowledge was hitherto known: wisdom—was attained. Bacon, or the Promethean, then, does not fancy knowledge, for it is simply a means to “interrogate, bend and break nature” in order to multiply the power of man towards “useful ends.” This is why Bacon chastised previous ages for “using as a mistress for pleasure what ought to be a spouse for fruit.”

To bring into fruition his insatiable lust for power, Bacon and his minions were “willing to do things hitherto regarded as disgusting and impious, such as digging up and mutilating the dead,” as Lewis tells us. In The Modern Prometheus, Victor Frankenstein does just that: he digs up deceased human and animal corpses in order to stitch together a grotesque and vile amalgamation of limbs and flesh: “I pursued nature to her hiding-places . . . I dabbled among the unhallowed damps of the grave or tortured the living animal to animate lifeless clay . . . I seemed to have lost all soul or sensation but for this one pursuit.” Bacon would be proud: for Victor expanded human power by intelligently arranging matter to create a conscious being!

What is Scientism?

Scientism is a dogmatic belief system that flows from Bacon’s Applied Science. For eons, knowledge—and consequently the application of knowledge—was thought to be holistic and comprehensive in nature, rather than fragmented and compartmentalized. Hence the “sciences” as we know them today, namely chemistry, physics, biology—and their applicative derivatives—were but one branch of learning known collectively under the discipline of “natural philosophy.” For ages, a “science” was but an academic discipline aimed at ascertaining the absolute Truth. St. Thomas Aquinas for example, called philosophy and theology the two “queens of the sciences”: all other academic disciplines like natural philosophy, politics, ethics, rhetoric, logic, math, and so on, originated from the former two queens. Only in the Modern Age has science become synonymous with not only natural philosophy, or the pure sciences, but also Baconian Applied Science, which aims solely at the increase of humanity’s power absent traditional moral concern. In Abolition, Lewis upheld Aquinas’s notion that the pursuit of the theologian and philosopher is to conform the soul to reality, while the magician and the applied scientist are in essence the same as both seek to conform reality to human will and desire. The way the world is moving, “science” is more and more the quest to “advance” human knowledge—and therefore power—not arrive at Truth. Scientism then, is by definition the rule of amoral applied science for the sake of advancing the power of the kingdom of humanity.

Victor Frankenstein as Prometheus

Just as Prometheus questioned the divine order, so too did Victor Frankenstein. In true Jacobin form, Victor condemned what he deemed the unjust and cruel nature of the world which he occupied. To this end, Victor embarked upon a quest to rearrange the natural order of things in a manner that corresponded with Victor’s his own mental fancy of the way things ought to be: “I had a contempt for the very uses of modern natural philosophy. It was very different when the masters of the science sought immortality and power; such views, although futile, were grand; but now the scene was changed.”

In the novel, Victor’s quest to conquer what he deems the injustice of death, is initially masked by altruistic notions about “helping his fellow creatures” in a cruel and ruinous world. Eventually, Victor’s “selfless” ideals dissolve, as he is consumed by his quest to animate inanimate matter through the haphazard arrangement of organic scraps, in a manner eerily similar to Prometheus—who molded man from clay as a power ploy to overthrow the divine order. Rather than acquiesce the necessity of death as the culmination of life, Victor boldly rebels against the cycle of death and re-birth, which greatly angers and emboldens him to extend the bounds of human knowledge, in a quest to extend humanity’s power over nature and its rhythms.

As the tale goes, once Victor breathed life into his creation by harnessing the power of lightning by apprehending and applying the physical laws of nature, he has an epiphany and recognizes the atrocity which he has committed. Upon this moment of cognizance, Victor decides to rest before attempting to erase his creation from existence. The rest is history: when Victor awakes, his “creature” is nowhere to be found and Victor is bewildered. Scorned by humanity for his grotesque outward appearance, the malleable creature devolves from benevolence to vengeful depravity aimed at his creator, who hated him and shirked his responsibility to inculcate just sentiments in his offspring.

Humanity at large is horrified by the creature’s ghastly outward appearance because it is apparent he is the incarnation of some unspeakable sin, and consequently reject his every attempt to garner affection. The creature’s vengeance and depravity ultimately culminates in the gruesome murder of all whom Victor holds dear.

In the novel, Victor is never fully conscious of the true gravity of his crimes against nature indicated by him chiding Walton to press on at the expense of his men to achieve “greatness” in the name of science and advancement. Victor, like many “monsters,” believes himself to be merely the malefactor of Fortune’s fickle nature: “I myself have been blasted in these hopes, yet another might succeed.” Delusionally, Victor measures his circumstances based on the effect, rather than the true cause and in doing so, absolves himself for acting upon his mistaken and corrupt ideals—ideals which Bacon himself would have been proud of. Nonetheless, Victor does realize he has been sentenced—like Prometheus—to a perpetual loop of futility as Victor conveys he is to pursue without cessation the malevolent fiend which he had created.

Modern Prometheanism

The momentous elevation of Victor above nature in an existentially dangerous manner, is an allusion to the excesses of radical Enlightenment rationalism that melded into what we know as “progressivism,” which was occurring in earnest as Mary Shelley penned Frankenstein. Progressivism stems from a quasi-religious longing for human beings to invest their efforts into something profound with teleological implications. Rather than emphasize the metaphysical which progressivism—with its Darwinist and materialistic roots—all but denies, progressivism seeks to channel its efforts towards the hope of some greater future that is enlightened and closer to perfection. In this quest, “progress,” rather than the attainment of Truth, became the ultimate end of human existence during the 19th century—and this pursuit of an “artificial Tao,” as Lewis calls it, continues today. Accordingly efforts to eradicate various evils like disease, alcoholism, and birth defects, for example, became the impetus for applied medicine, prohibition, and the Eugenics movement respectively. Mary Shelley rebuked these new doctrines as insidiously dangerous. As a faithful Catholic, she clung to much more conservative and traditional ideals that “struck at the root of evil, rather than hacked at its branches,” to use Henry David Thoreau’s famous idiom, that chastised the efforts of industrialists-turned-philanthropists.

Mary Shelley Laid the Groundwork for Thoreau, Huxley, Orwell, Lewis, and Others

Though Thoreau would later characterize modern technology as “improved means to unimproved ends” and Aldous Huxley would warn that the danger of technology is that it is but a “more efficient instrument of coercion,” Mary Shelley was perhaps the first to illuminate modernity’s insatiable appetite for temporal progress. Today perhaps greater than ever, humanity continues its quest to maximize its knowledge of the Baconian variety, in a bid to achieve a new age of heaven on earth, powered by the rule of applied science, or scientism.

A day does not pass when I do not come across an article that speaks of doing what was hitherto regarded as “disgusting and impious” such as geoengineering the climate to “save the planet” from Climate Change, as if the earth’s spawn is capable of saving that from which we arose. Likewise, genetically engineering chimeras with human and animal DNA so that their organs may be harvested for transplants is well underway, despite the fact that it reduces both life forms to “raw matter to be shaped and molded in the images of the conditioners,” like Lewis conveyed in Abolition.[1] Similarly, it seems as though Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the great collective pursuit of our time. For what reason or purpose I do not know, as it does not seem to solve any particular problem facing humanity, though it undoubtedly introduces a multiplicity of new ones. The late Neil Postman argued in Amusing Ourselves to Death that any tool must solve some prescribed problem, otherwise it is merely a superfluous technology and either distracts and anesthetizes, or is perhaps more even more sinister: AI seems to me the latter.

The specific case of AI presents a multitude of problems that Huxley’s Science, Peace, and Liberty elucidates, such as who wields this great advancement of human power? Big tech? The governments of the world? Either way, it seems unlikely that AI is to be used in a liberal and democratic manner, but rather to widen the gap between the ruling class and those it rules, because the average citizen will only have access to whatever technologies are made available to him or her, not the entirety of what exists. It seems robotic law enforcement for example—in our age of incessant legislation and centralization of government and corporate power—will not work for, but rather against the average citizen.

Perhaps most grotesque and inhuman of all are those miscreants working to achieve an eternal existence in the temporal realm: across the globe, transhumanist applied scientists are at work seeking to achieve a singularity between man and machine. Like Victor Frankenstein, these deranged individuals are working to preserve the dead via cryo technologies in order to delay the decay of the brain so that in the not-so-distant future, the brain may be synchronized with a computer in order to “live” forever. While that to me does not constitute life, to the Modern Promethean—who will never cease to advance his or her power—it is close enough.

Mary Shelley was a prescient sage. While we should listen to our sages, human hubris and vanity knows no bounds. Though Frankenstein remains the most popular gothic novel in the English language 200 years later, we have failed to grasp and apply its motif as we attempt to ascend to the heavens via our own Tower of Babel that is nearly complete in 2019.

[1] Garrett Dunlap, “The End of the Waitlist: How chimeras could solve the organ transplant problem,” Science in the News, March 9, 2017.