The Historical Case Against Censorship: Why free speech matters.

(Originally published in 2021).

“If all printers were determined not to print anything till they were sure it would offend nobody, there would be very little printed." -Benjamin Franklin

“Information is the currency of democracy.” -Thomas Jefferson

“The books that the world calls immoral are books that show the world its own shame." -Oscar Wilde

The return of an old foe

Censorship is a recurring plague upon the free society that has once again reared its ugly head in recent times. I originally penned this piece nearly three years ago, upon the first major wave of “Big Tech” censorship that began with Alex Jones, but has now culminated in both the incessant “fact checking” by so-called “impartial” bodies and the permanent removal of the sitting president of the USA (and many other conservative voices) from Twitter and other online platforms. Whatever you may think of him, this action speaks volumes as to the state of American civilization, which to me seems all but a distant memory and a great idea, if not an actuality. These social networking companies including Google, Facebook, Twitter with founding ties to government intelligence agencies, that are subsidized by taxpayers, and granted legal immunities as platforms under Section 230 (despite acting as publishers), are actively stymieing and stifling dissent in the wake of an extremely controversial and contentious election under the guise of “community guidelines violations,” that are oftentimes arbitrarily and selectively enforced.

A very brief history of censorship in the West:

Censorship has always existed in one form or another.

Since the advent of organized society, those in control have sought to stifle dissent and prevent the dissemination of subversive ideas at any cost. History is ripe with examples of the former premise: from the punitive suppression of the venerable Socrates that culminated in his suicide—to the Burning of the Vanities in Florence—censorship has long been a thorn in the side of the free society. It is by no mistake that the First Amendment to the United States Constitution protects freedom of speech, press, religion, petition, and assembly. Astute and learned men, the Founding Fathers of the United States sought to construct a society based on empirically verifiable and self-evident truths. For them, one of history’s great lessons was that the censorship of information and ideas was antithetical to a free society, where the individual ought be at liberty to pursue his or her own “happiness” through just means. Drawing from European history—and world history at large—the classical liberal founders understood that liberty and justice could not exist in the same neighborhood as censorship.

Savonarola preaching—painting by Ludwig von Langenmantel.

The Pre-Modern Order

Europe during the Renaissance was a very chaotic place. Compared to the Middle Ages which were relatively peaceful and stable, the Renaissance was an age of political centralization which led to wide-scale Continental and colonial wars, like the Thirty Years War. The political economy of the Middle Ages was feudalism, which consisted of landed feudal lords and vassals that pledged oaths of fealty to them. The lords were sovereign in their fiefdoms, but had to pledge their loyalty to greater, albeit loosely organized, kingdoms. During the Middle Ages, there were few unified kingdoms or states as we think of them today, but rather a conglomeration of small duchies that reigned over their own realm. During the High Middle Ages in what is now France for instance, there were the duchies of Brittany, Aquitaine, Saxony, Normandy and many more. To maintain stability, the monarch of France had to remain in good favor with his nobles and the nobles had to temper their ambition to remain in good standing with the monarchy. This order led to constant quibbling and small-scale raids and skirmishes, but few large-scale “total” wars like we moderns are accustomed. Conflicts like the Hundred-Years-War, are considered by scholars to be modern in nature, rather than medieval. The Church, which was entirely Catholic at this point in history, also factored into the Medieval Order. While England was organized similarly to Medieval France, urbanized Italy was not unified in the least, but rather consisted of sovereign city-states like Florence, Venice, Milan, Naples and the Papal states. One could say the Medieval Order then was decentralized because power was delicately juxtaposed between equally powerful rivals; in this way, stability was maintained between the Church, populace, various lords and inept kings.

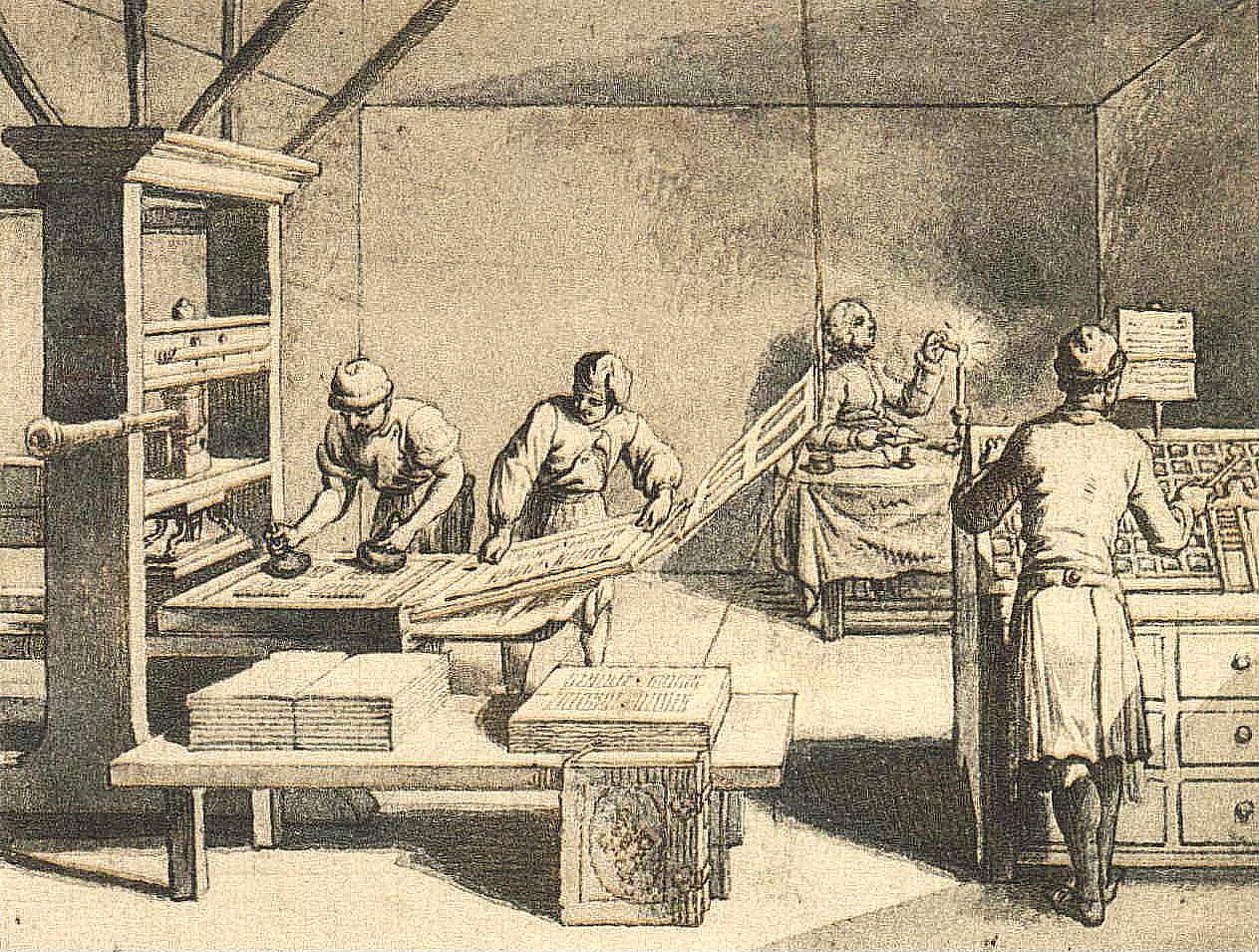

The Advent of the Printing Press Necessitated Censorship For the Ruling Class

With the advent of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in the 15th century, the written word could be distributed more rapidly to a much wider audience than ever before. For better or for worse, this dissemination of information and ideas led to a boom of literature deemed by the authorities as subversive and heretical. With Renaissance Humanism, led by authors like Francisco Petrarch, Giovanni Pico Della Mirandola and Desiderius Erasmus now on the horizon, it was clear the Catholic Church’s monopoly on the written word and ideas was at an end. At the dawn of the Renaissance in Europe (circa 1350), the Catholic Church had already amassed a bountiful reputation for abuse. Although the Church was able to recover from the Pornacracy and various schisms, the advent of the printing press set the stage for new and wide-spread heresies to fester.

The printing press allowed for the wide dissemination of ideas, near and far.

“Heresy” literally translates to wrong belief and denotes any belief that runs contrary to established Church doctrine. In the Middle Ages, the Church had a monopoly on scripture because most of the peasantry was illiterate, books were exorbitantly expensive, and the Bible had yet to be translated into the language of the people. This state of affairs changed in the 14th century when Oxford theologian and dissenter, John Wycliffe, translated the Latin Vulgate into the English Bible. Later, Martin Luther and others “protesting” Church authority would follow suit by translating the Bible from the Latin Vulgate and Greek Septuagint into the native language of their respective peoples. Since the Bible could now be read by the populace at large, Church rule was undermined leading to the Protestant Reformation and subsequent Catholic Counter-Revolution. While Martin Luther could be said to be the instigator of the Reformation, John Calvin, Huldrych Zwingli and other Protestant dissenters who followed in his wake were equal part political revolutionaries. United in their opposition to papal authority and Church dogma, Protestant reformers championed scripture as the only path to the divine. The emphasis on scriptural authority—coupled with an increasingly literate public with newfound access via print culture to a proliferation of religious and political ideas—undermined the Catholic Church’s grip on society, tearing Europe apart at the seam. In the power vacuum that ensued, monarchs across Europe asserted themselves in a bid to expand their power. No longer did the monarch serve the interest of the Church, but rather the Church was subject to great scrutiny and intervention by the monarchy.

The Inquisition as a Means to the Maintenance of Power

In Catholic countries like France and Spain, persecution of protestants and other religious dissenters commenced, epitomized by the French Wars of Religion. During the late 15th and early 16th century, Spain was the preeminent power in Europe by virtue of plundering the riches of the New World. To secure their rule, Ferdinand and Isabella of the joint-kingdoms of Castille and Aragon, petitioned Pope Sixtus IV in 1478 for permission to launch a judicial entity tasked with combating “heresy.” The monstrosity which was spawned by the unholy melding of Church resources with Spanish might would infamously come to be known later as the Spanish Inquisition. Using Draconian measures, the Inquisition burned its way through Europe, beginning in Spain, before spreading to France, Portugal, Italy and even Mexico and Peru in the New World. Though the Spanish Inquisition began as a clerical institution, it quickly became a secular tool—opposed even by the pope himself—wielded to slash opposition and pander to hysteria. Depending on the severity of the accusation, torture, confiscation and intimidation could be employed. In rare cases, “auto da fe” was its conclusion, though this was usually carried out not by the inquisitorial tribunal, but by the increasingly absolutist secular kingdom. Victims were generally Protestant, Jewish, dualistic, or Muslim—though Catholics like Ignatius Loyola and Desiderius Erasmus were similarly deemed culpable for their “wrong” beliefs.

The burning of a Dutch Anabaptist, Anneken Hendriks, who was charged with heresy in Amsterdam in 1571.

Further constraining thought and expression, the Catholic Church issued the first “Index Librorum Prohibitorum,” or Index of Banned Books, in 1559 after accepting the efficacy of pre-censorship at the Fifth Lateran Council in 1515. In Catholic countries like France and Spain, the Index of Banned Books pre-censored the printing of books that ran counter to Church orthodoxy, in addition to condemning heretical books that had already been published. Notable authors once censored by the Catholic Church at one point in time include: Desiderius Erasmus, Niccolò Machiavelli, Michel Montaigne, Rene Descartes, Blaise Pascal, Voltaire, Jean Jacque Rousseau, Galileo, Marquis De Sade, Victor Hugo, Peter Abelard, John Calvin, John Milton, Martin Luther, Baruch Spinoza, John Locke, John Stuart Mill, Jonathan Swift, Marquis De Condorcet and many more. With the quality of authors censured by the union of the Catholic Church and absolutist states of early-modern Europe, it is apparent that Truth was the greatest victim of censorship: for the people of the world were robbed of the wealth of knowledge by an acrimonious minority whose cunning methods successfully culminated in the acquiescence to censorship by an ignorant public. The Inquisition and censorship in general were not simply a case of misguided religious zeal. Rather, religion served as a façade for the powers of the day to expand their power over the populace. Christianity, in its essence, champions love, empathy, grace, humility, tolerance, brotherhood, and the sacredness of the individual’s eternal soul, among other esteemed virtues. When critics point to religion as the cause for pandemonium in early-modern Europe, they fail to recognize the sole cause of conflict was persecution stemming from intolerance and censorship. As in in perpetuity, the lust for power caused the “religious” wars that tore Europe apart. Later authors—like John Locke, John Milton, Voltaire, Adam Smith, Alexis Tocqueville, and others—understood that in order for the tyranny of early-modern Europe to be supplanted by liberty, intellectuals and the public at large must be free to exchange information and ideas in the public sphere, unabated and uninhibited by censorship.

John Milton’s Aeropagitica applied to our digital age:

“This is true Liberty, when free born men, Having to advise the public may speak free. Which he who can, and will, deserves high praise. Who neither can nor will, may hold his peace; What can be juster in a State then this?” —Euripides

The quintessential text against censorship, remains John Milton’s Areopagitica, which was delivered orally to parliament in 1644 during the English Civil War. With his defense of free speech, the sagacious Milton laid a cornerstone that later thinkers would integrate into the foundation of a political philosophy that we now call classical liberalism.

By virtue of being a rational human being, all are entitled to share ideas in the public arena.

The major premise of Areopagitica, aptly named for a speech given by the Athenian statesman Isocrates condemning general censorship in the 4th century BC, is that human beings—being rational and capable of reason—must be free to exchange information in the public marketplace of ideas if Truth, and therefore virtue, is to be attained. When this process is interrupted—through coercive measures as in censorship, or subversive ones like modern propaganda stemming from a perfect applied psychology—the common good is irreparably harmed as falsehood is easily misconstrued as truth.

The necessity of a vibrant public sphere:

Milton believed that every individual was not only entitled to his or her own ideas, but also compelled with a sense of duty to share their findings with others:

“And how can a man teach with authority, which is the life of teaching, how can he be a doctor in his book as he ought to be . . . whenas all he teaches . . . delivers, is but under the tuition . . . (and) correction of his patriarchal licenser, to blot or alter . . . he calls his judgment?”

Milton would be appalled and disconsolate due to our current societal climate with the manifestation of trivial newspeak, as represented by so-called advent of “fake news.” This alleged crisis has subsequently led to the calls by some for corporations or the state to establish “the facts” on any given matter within their digital platforms, which they have done with now ubiquitous, “fact checkers.” Milton, perhaps too confident in the universality of human reason, asserted that unabated access to information was not a privilege, but rather a natural right:

“When God gave him (Adam) reason, he gave him freedom to choose, for reason is but choosing.”

“he who kills a good book, kills reason itself (and) the image of God.”

By way of historical antecedent, those who favor censorship are in bad company.

Specifically, Milton was protesting the licensing of new books by Cromwell’s Puritan Parliament, which pre-censored and post-censored certain works deemed fallacious, immoral, vulgar or subversive. Milton contended the imperative to separate truth from falsehood and fact from fiction, fell solely on the on the outcome of discourse taking place in the marketplace of ideas, as he conveyed:

“Where there is much desire to learn, there of necessity will be much arguing, much writing, many opinions; for opinion in good men is but knowledge in the making . . . . A little generous prudence, a little forbearance of one another, and some grain of charity might . . . unite in one general and brotherly search after truth, could we but forego this prelatical tradition of crowding free consciences and Christian liberties into canons and precepts of men.”

Censorship is the product of an audacious and self-aggrandizing claim of moral authority and superiority: for what autocrat or authoritarian oligarchy (or technocrat) can morally and rationally legitimize such power over others? Historically and presently, those who rule through despotic means have proven time and again that such censorship is solely for the sustenance and expansion of power and influence, even when masked as religious zeal or moral concern. When discussing censorship, Milton explicitly notes the example of the Catholic Inquisitors—whose nefarious methods are outlined above—while illuminating similarities the Puritans shared in methodology with their so-called foes. In Milton’s age, governments prevented voices—both noble and ignoble—from being heard. In our age, big tech’s monopolization of digital mediums allows the new “masters of man” to circumvent First Amendment protections on speech and expression (under the guise of acting as a private entity), though it undoubtedly acts the same. While Milton was familiar with the abuse of state-power, corporate power should be treated similarly. What the state and the multi-national corporations that it subsidizes and protects have in common is an interest to expand their own power and wealth. The people in contrast, simply wish to exist free from the horrors of arbitrary coercion and tyranny, which may present itself in many forms including COVID lockdowns and mandates delivered from on-high without the consent of the governed.

Milton’s Assertion: Truth Will Win Out

Ascertaining truth is always in the interest of the populace, but not necessarily government and its step-sibling: the corporate media. Truth then, cannot easily be apprehended through media censorship, whether overt or clandestine as is in the case of TV news and increasingly censored internet algorithms. Naïve or not, Milton upheld that Truth—regardless of censorship—would eventually win out despite censorship:

“ . . . though all the winds of doctrine were let loose to play upon the earth, so Truth be in the field, we do injuriously by licensing and prohibiting to misdoubt her strength. Let her and Falsehood grapple; who ever knew Truth put to the worse in a free and open encounter?”

In many cases, Milton’s assertion has proven to be correct. A historical example of this could be chattel slavery: which although not entirely abolished worldwide at present, is universally recognized as morally repugnant. By actualizing and carrying to logical conclusion, the doctrines of liberalism and Christianity, slavery has been demonstrated to violate the inalienable natural right to life and liberty possessed by each human being, by virtue of simply being a human being. Thanks to the efforts of liberals like Frederick Douglas, Abraham Lincoln, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau and others, the universality of natural law was able to triumph over wickedness. In the aforementioned case, Truth won out in the end. For the sake of American liberalism, Milton must be correct on all instances where Truth and Falsehood grapple, lest the American people will continue to succumb to party politics and “men of the system,” thereby becoming increasingly disenchanted from the liberal principles established by our forebearers. If Milton was wrong, America will become a nation of Winston Smiths: rejecting Truth despite the conclusions of our own reason.

Error Can Sharpen Our Appreciation of Truth

As has been said, Milton asserted a vibrant public sphere rife with debate—free from slander, hostility, and censorship (which fosters division and hatred)—would, more times than not, arrive at Truth. Nonetheless, the process of discourse and dialogue—utilized as vehicle to ascertain Truth—would sharpen the appreciation and understanding of Truth:

“if the men be erroneous . . . what withholds us but our sloth, our self-will, and distrust in the right cause . . . that we debate not and examine the matter thoroughly with liberal and frequent audience; if not for their sakes, yet for our own? . . . they may yet serve to polish and brighten the armoury of Truth.”

The result of a methodical contemplation of new ideas—however asinine or vulgar—culminates in a profound understanding. By considering ideas contrary to those presupposed to be true, the individual now has a much greater appreciation for the specific reasons why either the new or established truth is indeed true. Complex understanding—as opposed to dogma—breeds civility rather than strife, which is woefully lacking in contemporary American society.

Cloistered Virtue is Not Virtue

In his condemnation of Parliamentary censorship, Milton elucidates the profound truth that virtue is reflective of an internal condition and therefore vice cannot be legislated or censored away:

“ . . . rightly tempered (passions) are the very ingredients of virtue? They are not skillful considerers of human things, who imagine to remove sin by removing the matter of sin . . . when this is done, yet the sin remain entire. Though ye take from a covetous man all his treasure, he has yet one jewel left: ye cannot bereave him of his covetousness. Banish all objects of lust, shut up all youth into the severest discipline that can be exercised in any hermitage, ye cannot make them chaste.”

By echoing Aristotle’s Golden Mean, Milton argued that the equilibrium between two opposing actions must be found. Lust, for instance, must be balanced with temperance and moderation to not be driven entirely by the flesh, but also to refrain from being reclusive and cloistered. This balance for Milton then, occurs within the individual as they shrink and grow, fail and succeed; the attainment of virtue then, is an extremely personal and private one, which should be free from state overreach. St. Augustine is the historical archetype for this notion: for it was his salacious youth that allowed him to recognize his need for the Divine, as he conveyed in Confessions. Though Milton’s argument rings true, he was not oblivious to the fact the powers of any age, seek to inculcate moral outrage as a guise to expand their power. In this case, moral concern masks the desire to censor opponents—who in Milton’s epoch—criticized the status quo on nearly everything: from tyrannical governmental and religious institutions, to economic and social systems. Posterity demonstrates why all individuals, must be free to exchange information in the public marketplace of ideas, where any new theory or conjecture will be tested rigorously through rational means.

When Will It End?: Censorship Sets a Dangerous Precedent

Give an inch, and those in power will take a mile: 2020 proved the veracity of this idiom, which is why it is repugnant to hear opponents of those who have been recently censored cheering in the streets: for those cheering may be the next to be censored. History has demonstrated time and time again that those in possession of some truth are likely to be censured if they are in opposition to the powerful and ambitious. The lust for power is not easily satiated and it will employ both surreptitious and punitive means if necessary. People on the left forget that as recent as the 20th century, socialists, anarchists, and libertarians alike have been imprisoned, beaten and defamed. The censure of one, is the censorship of all. Nonetheless, the cessation of individual liberties to big brother or big business is not likely to end with those who are simply “offensive and vulgar.” John Milton understood this downward spiral, when he said,

“If we think to regulate printing, thereby to rectify manners, we must regulate all recreations and pastimes, all that is delightful to man. No music must be heard . . . but what is grave and Doric. There must be licensing of dancers, that no gesture, motion, or deportment be taught our youth, but what by their allowance shall be thought honest . . . It will ask more than the work of twenty licensers to examine all the lutes, the violins, and the guitars in every house; they must not be suffered to prattle as they do, but must be licensed what they may say . . . there are shrewd books, with dangerous frontispieces, set to sale: who shall prohibit them, shall twenty licensers?”

Easily misguided moral outrage and subsequent censorship, i.e., cancel culture, has no place in a free society. If one finds something offensive there is a simple solution: turn off the offensive content, put down the offensive book, or flip the webpage and move along! There is much that offends every human being, as we are all uniquely different and the solution for idiocy on all fronts is kindness, civility, basic decency, and a steadfast clinging to the American principles enshrined and codified in our founding documents that must be common and applicable to all equally under the law. As for me, I do not wish to live in such a prodding society that is becoming increasingly filled to the brim with tyrannical and omnipotent, “moral-busybodies.”