Tolkien’s long defeat is best understood in his own stories. For those familiar with Lord of the Rings, the story seems to be victorious. In the end, the “Ring of Power” is destroyed and all is well. The larger mythos of Middle Earth, however, tells a different story. Sauron, the great villain we see defeated, is a minor antagonist compared to the great villain Melkor, who created Sauron and still lives at the end of the story.. The War of the Ring only culminated in a glimpse of victory, it is far from over, and true evil continues its work. Essentially, this idea of the long defeat is an acknowledgement that man, on our own, will not win the cosmic war against evil. We will die while evil still walks the earth. Yet defeat is different from surrender. The long defeat is the dreadfully long history of men and women of faith desperately fighting without a thought of surrender. They may see some small victory in their time, but their will cannot ultimately turn the tide against evil. Today we fail to ascertain this and only live for small victories without eyes for the long defeat. We are unprepared to reach the top of our proverbial Mount Doom, where it is apparent that all created things will fail to eternally stand up against evil.

The Ring of Power

To begin, evil should not be regarded as that which is external to us. There is much that lurks within us which remains unknown to us. In Jungian terms, this is the Shadow: all that remains hidden from consciousness. Though not by nature evil, the Shadow is overwhelmingly immoral, or at least undesirable. It is where all the things we cannot bear to know about ourselves reside, and the most difficult thing to know about oneself is how evil we truly are. Tolkien’s long defeat does not make assumptions about the source or location of evil, and the entire war against Sauron comes down to Frodo’s ability to resist the ring, the Jungian Shadow as it were. Therefore, the battles across Middle Earth are waged not for victory but to buy time for Frodo to fight the evil within himself, and he fails.

Psychology has long had the task of developing an understanding for human evil, and is a task that became increasingly popular following the horrors of the Second World War. Most people--in an attempt to protect their sense of self--create distance between the concepts of “good” and “bad”, place themselves firmly amongst the good. The commen man thus contends that if he had lived in WWII Germany, he would have resisted the Nazis by hiding Jews--a preposterous supposition. All the wisdom of religion and psychology is extremely clear: each person is capable of remarkable evil. The oft referenced Milgram study and Stanford prison experiment are radically oversimplified to make this point, but alas, the overarching motif remains true. I may struggle to believe it, but I am capable of profound evil; I too am capable of participating in genocide. If one thinks differently of himself or herself, then they deceive themselves in the worst way. This deception is precisely what the Jungian Shadow refers to. It is believing that we would have moral success where others have moral failure. To bring the evil residing within each of us into consciousness is overwhelming and intolerable, so it stays in Shadow.

Whether we see it or not, the devil lives within each of us. So, what do we do with this Shadow we probably cannot see? According to Jung, we begin by developing awareness of the Shadow without identifying with the Shadow. This distinction is key; to be aware of the shadow is to know that we have incredible capacity for evil, to identify with it is to say, “I am my capacity for evil” and to take that evil into our sense of self. Identifying with evil is the beginning of acting on evil, and must be avoided. Acknowledging it, however, is the honest appraisal of ourselves. It is moving things from the Shadow into the light, which allows us to make the active choice to fight and purge the evil once we see it. We cannot fight what we cannot see.

Once everything in the Shadow has come to light, we must not make the dreadful mistake of assuming it all hateful. Crucial to this conversation is the Augustinian concept of Evil. Evil is not an essence in itself, but rather an absence of the life-giving force, i.e. God who is the “Form of the Good.” It does not have the power of creation, so it destroys and mars the good of creation. This suggests that the war against evil is best fought with the realization that even evil speaks to something true. Lust is a relational sin that wants others so badly it consumes them. From a psychoanalytic standpoint, libido is the drive to relationship, as relational needs underlie the desire for sex. This overwhelming desire for relationship tells us that we are communal creatures, who long for companionship. This is a good and right thing, but it becomes sin when feeling alone becomes so intolerable that we make other people into easily consumable objects so that we can mitigate that misery. Since no created thing can be evil in itself, but rather a corrupted good, we must confront and even hate our incredible capacity for evil without hating the self or the underlying goods of creation. Hate lust, do not hate needing companionship. This differential is key in discerning what is the enemy from all the other things we struggle to reconcile within ourselves.

Now we can see clearly, so we set ourselves against evil knowing we will lose. In Alcoholics Anonymous, no matter how long you have been sober, you introduce yourself by saying “I am an alcoholic.” Perhaps this is a bit too close to identification, but it acknowledges that sobriety can be lost in an instant. We will forever do battle with that addiction till the day we die because we do not have the power to eliminate it entirely. A single single weary day can cost decades of sobriety. Just as sobriety does not cure alcoholism, neither does marriage cure lust. Any vice can be substituted here but the point remains the same: fighting the evil within us is not the same as vanquishing it. So we do combat, setting ourselves against the Shadow within us that would gorge on sex, violence, substances, and egoism. We bring them into our home, not as pets, but in cages, and we let them starve. We take them in so we can see them, starve them, and always be mindful of where they are at and how they act. And we are ready, and a moment’s notice, to do battle again should they break out of the cage.

So we are left with the paramount question, “Why bother?” If, as I say, we cannot have victory, why do the back-breaking labor of dragging vice from Shadow to light and engaging it in grueling combat? I say there are two reasons, a greater and a lesser. The lesser is that we will have to answer for ourselves. When Frodo wishes away living in the time of War, Gandalf replies, “So do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.” There is much we cannot control: when, where, and how long we live, but we will have to answer for what we do with the life we have been given. If all defeat is equal, then this would not matter. The answer is loss. The measure of defeat, however, is not equal. Waving the white flag is fundamentally different from fighting to last man. The fight should be to prioritize not great acts, but rather small acts done with great love. The daily regiment of setting ourselves against the evil within us is a small act, but it can and should be done with the greatest love. This love is for the Divine, others, and the self. It loves the divine by obeying its commands, it loves others by treating them honorably and virtuously, and it loves the self by seeking only the best for itself. This is radically different from the love of the present day, in which pride and egoism masquerade as self-love, and call itself virtues. True, we must love ourselves, particularly if we are to “Love our neighbors as ourselves.” However, love is not soft and comfortable, as many would have us believe. Nor is it indulgence or happiness. Love is ruthless in its endeavor to perfect, so we shall be the same.

This distinction in love begins the division in kinds of self-knowledge being pursued. Modern culture and it’s love of pop-psychology personality tests rarely speak to the Shadow. The Meyers-Briggs Type Indicator does not tell people the vices they must set themselves against. They are instead, a form of self-aggrandizement. This is contrasted with the self-knowledge encouraged by religion and psychoanalysis, which would have us confront the devil and see our own face. When love is soft, it celebrates small, irrelevant things we have discovered about ourselves. When love is terrible, it forces us to confront the evil we have been desperately avoiding.

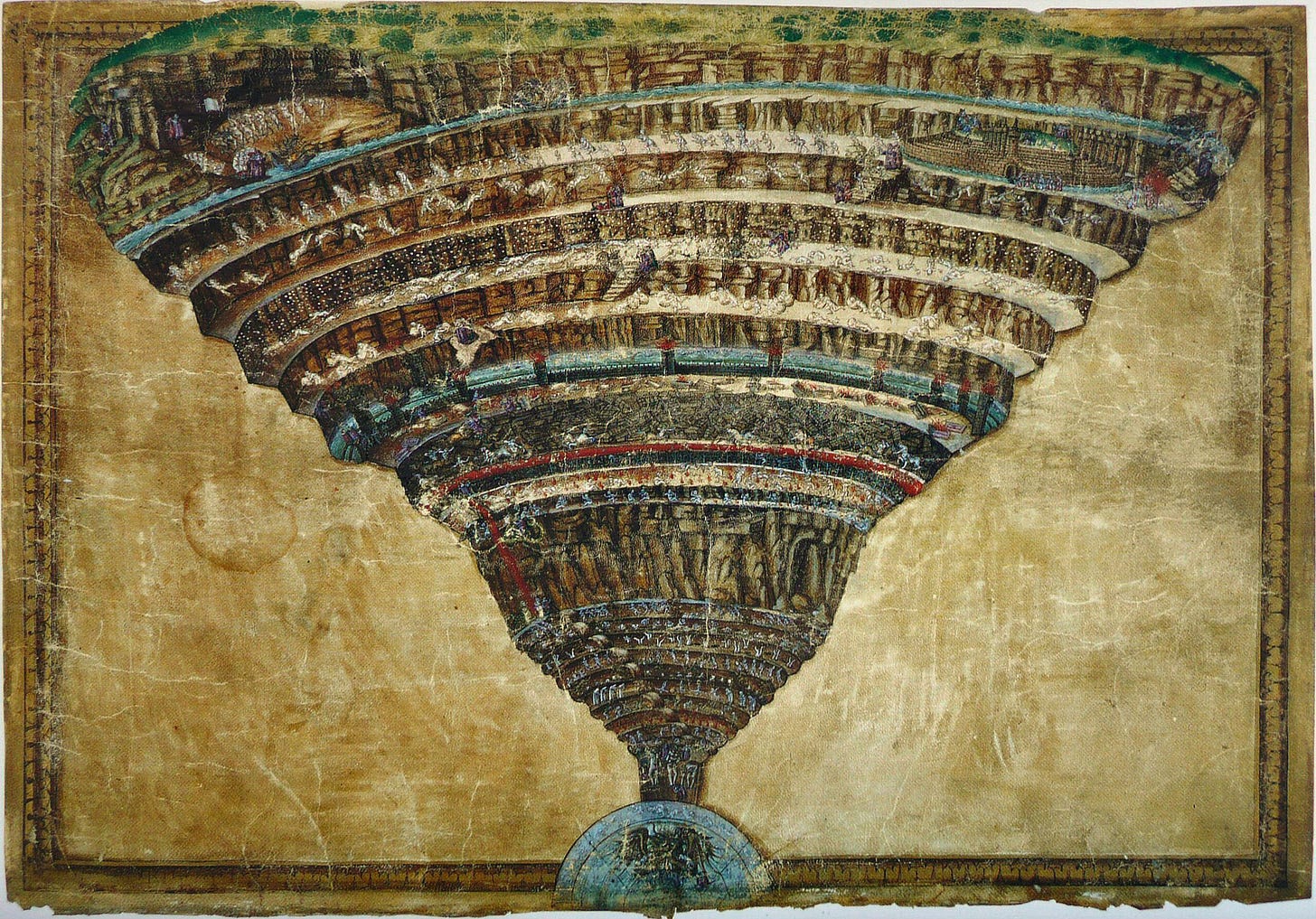

A Map of Hell in Dante’s Inferno, by Botticelli

This shift towards a soft view of love is not wholly in the wrong. It is responding to a force of destruction, not perfection. So all that was being destroyed was given affection and compassion and kindness, without regard for what exactly was being destroyed. We now live in an epoch that would not distinguish between love and affection. As such, all self-knowledge is framed positively rather than negatively. Certainly, there is a place for knowing the divine image within the self, but Christ descends into hell before His ascension. Dante must meet Satan before he experiences Beatitude. Now we have come full circle, and returned to the Shadow. We too must go into the depths of ourselves before we can live in glory. The light we carry will, by nature, drive out the Shadow if we do not cover it. So we need not concern ourselves with all that is good within us, for to drive out the Shadow is by nature to shine the light, but if we tolerate the Shadow, we cannot bear light. So, for the love of light, of divinity, of others, and of self, we do not tolerate hidden things. We expose them, and where necessary prepare ourselves for the grueling life of fighting a long defeat.